The prospect of global thermonuclear war haunted humanity for 50 years during the Cold War.

And while the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s largely cast such an all-encompassing scenario into the relics of a bygone age, the threat never disappeared.

Today, the most likely scenarios include a skirmish along the India-Pakistan border raging out of control, or a nuclear mistake — a computer hack, unstable leader or miscommunication triggering a missile launch.

Or as some have questioned in a grim scenario, could the U.S. and Russian militaries, pushed to the brink by a war like that seen in Ukraine today, reach to their nuclear stockpiles?

One 2019 simulation from Princeton’s Science and Global Security program modelled how such a conflict might take place.

With over 12,000 nuclear weapons combined, the researchers looked at how such a war would escalate. Based on the two countries' current nuclear strategies, the group looked at how long it would take to move from a conventional to a nuclear war and how many people would die.

Beginning with a nuclear warning shot from the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad, NATO retaliates, with a single tactical nuclear strike. Within three hours, Europe, the United States and Russia are engulfed in a full-fledged nuclear conflict as hundreds of short-range missiles and air strikes are launched at each other's bases.

With Europe destroyed, the U.S. launches 600 warheads from silos and submarines toward Russian nuclear forces. Russia responds.

To prevent the other side from recovering, both NATO and Russia target dozens of cities and economic centres with five to 10 warheads each.

In the end, the modelling found that over 34 million people would die immediately, with nearly 60 million more left injured.

But it’s the deaths that come after that would be truly debilitating to the survival of humanity and the nearly nine million other species thought to exist on Earth.

Nuclear fallout at sea

Last week, a new study published in the American Geophysical Union journal AGU Advances reran old models of a global nuclear winter dating back to the 1980s — this time plugging in the numbers into a modern climate circulation model.

What they looked to answer: how would a nuclear war affect the planet’s oceans, and in turn, the life that springs in and from them?

Using the Community Earth System Model, the researchers determined the short- and long-term effects of the nuclear fire storms after the missiles landed.

That meant measuring how the debris from that destruction would be scattered into the atmosphere as black carbon, or soot, and how it would affect the oceans.

In the worst-case scenario, nuclear war between the U.S. and Russia breaks out on May 15. With most of their arsenals spent bombing each other's cities, 150 million tonnes of soot is launched into the atmosphere.

That would block out 70 per cent of the sun’s short-wave radiation and drop average global surface temperatures by seven degrees Celsius over the first months.

“It's coming from burning cities,” said Cheryl S. Harrison, an oceanographer at Louisiana State University and the lead author of the research. “You have all these different military targets. A lot of them are near cities. And so you have large fire storms from burning cities.”

In the Northern Hemisphere, and especially in places like Canada, those temperatures would crater even more, leading Arctic sea ice to clog normally ice-free areas.

That, in turn, would decimate several fish species important to coastal fisheries. Harrison said the plummeting temperatures would hit a lot of bottom-dwelling fish immediately. Unlike tuna, species like halibut would likely struggle to swim to warmer waters and would suffer as a result.

Salmon, meanwhile, would likely struggle to make it up and down B.C.’s waterways as they increasingly freeze over.

But even species at sea would struggle to survive.

In the first few years after the nuclear war, the sky would be darkened by the soot of hundreds of cities. With the sun largely blotted out, phytoplankton would die off, erasing the base of the oceanic food-chain across much of the world.

“There's not going to be food for them,” said Harrison.

Those humans who survived, mostly in tropical areas, would inevitably have to turn to wild-caught and farmed seaweed, notes the study.

Small conflicts lead to devastating nuclear winter

Harrison and her colleagues looked at several scenarios, from the detonation of a few hundred warheads in a limited conflict between India and Pakistan, to thousands of warhead strikes in a full-blown war between Russia and the United States.

Even in the smaller (and most likely) nuclear skirmishes between India and Pakistan, aerosols blasted into the upper atmosphere reached levels seen in the 1815 Indonesian eruption of Mount Tambora, the largest volcanic event in recorded history.

“We have the year without a summer,” said Harrison, referencing 1816. “Aerosols from the volcano [go] into the upper atmosphere, they get distributed globally, and they cool the planet — and they cause famine.”

The summer of 1816 saw everything from widespread crop failures to red sunsets. On the shores of Lake Geneva, 18-year-old Mary Shelley was kept indoors by the inclement weather. When friend Lord Byron proposed a contest to write the scariest story, she penned the famous novel, Frankenstein.

A nuclear war, however, would be much more frightening — and deadly.

Unlike a volcanic eruption, scientists think the aerosols in a nuclear war would be much finer, and therefore, would stay aloft in the atmosphere for much longer.

Harrison said a medium-sized regional nuclear conflict involving 4,400 100-megatonne weapons would lead to a 10-degree Celsius crash in average global temperatures — colder than the last ice age.

In some northern latitudes, it would be twice that.

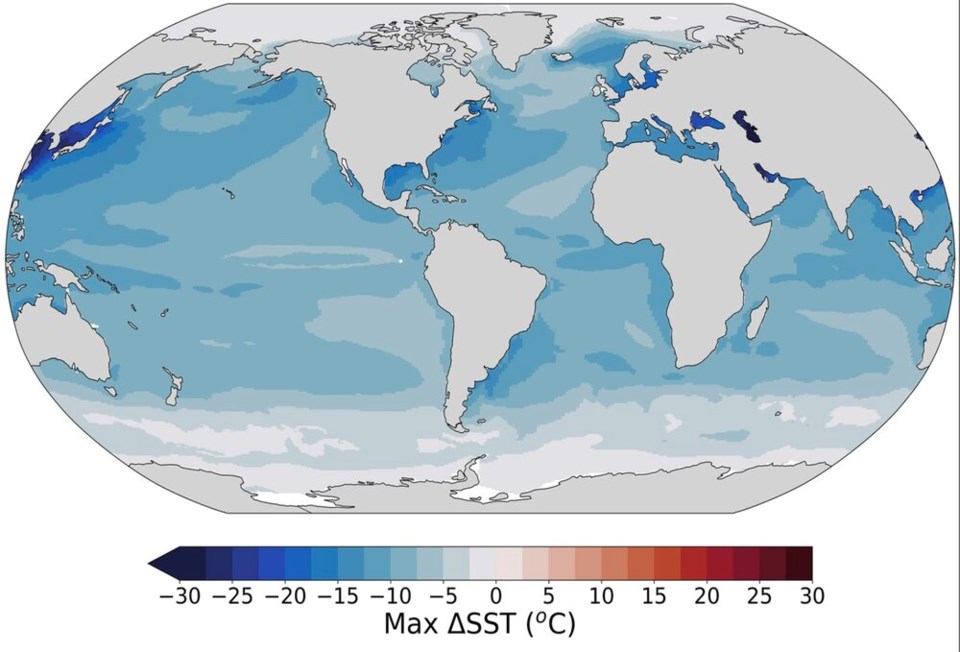

At that scale, the modern climate model found ocean temperatures would plummet 30 C in some parts of the planet, leading to massive increases in sea ice formation in the seas of the Korean Peninsula and Japan.

The sea around Canada’s Maritimes would dip by more than 15 C, whereas on the West Coast, sea temperatures would drop by something closer to 10 C.

“The shallower parts of the ocean near land would get even colder,” said Harrison. “You could have sea ice all over... the land is even colder than the ocean.”

Modelling fine-tuned through wildfire, major earthquakes

Modelling a hypothetical nuclear war presents a lot of uncertainty, mostly due to the fact that we don’t have a lot of precedent around such a conflict.

To fine-tune their calculations, the researchers turned to accounts from the 1908 San Francisco earthquake, where eyewitness accounts of the subsequent firestorms speak of vast plumes of dark soot rising into the sky.

As the dark plumes absorb radiation, they get warmer and continue to gain altitude.

“There are these eyewitness accounts of this wind from all around going toward the city as this air was going up,” she said. “And we have some observations of recent big forest fires on how the smoke works.”

Harrison added: “It's a model, so it's imperfect, and you can always do more. But the whole point of this is that even if this is probable... still these very small nuclear wars have a very large impact.”

A potential climate rebound effect

After a “Nuclear Little Ice Age,” recovering from the frigid temperatures would likely take decades on the sea surface and hundreds of years in deep ocean habitats.

In the Arctic, Harrison and her colleagues concluded a rebound to today’s temperatures would take thousands of years.

In their study, researchers found that human-caused climate change, while not simulated in their model, could mitigate some of the nuclear-triggered cooling, and the resulting ice expansion.

But Harrison warned that after a period of cooling, global warming could come roaring back. She points to a 2017 study looking at the effects of a large volcanic eruption.

Looking at volcanic activity in the past, the study found the intense cooling associated with the spewing of volcanic soot was quickly followed by another period of heating.

In other words, over the long-term, there are no guarantees a nuclear winter would balance out human-caused global warming — and it could offer a one-two punch to many species across the globe.

Even with the sun blotted out, the planet’s oceans would still become acidified by the existing carbon in the atmosphere, “and you're still dissolving the shells of critters on the West Coast, which affects the food chain,” said Harrison.

“You're going from a cold to like really hot again, and then that really affects animals like us and others... Billions of people would die.”

Call to ban nuclear weapons

Harrison and her colleagues are working to get their data into the hands of social scientists, policymakers and the public.

They are now in the process of creating a database that details the fallout nuclear war could have on ocean life, the expansion of sea ice, and in an upcoming study, how crop failures would affect the ability of countries to feed themselves.

According to a pre-print version of the study, which is led by a colleague and has not yet been peer-reviewed, most countries in the Northern Hemisphere would see catastrophic crop failures.

Even in a limited conflict between India and Pakistan, 16 million tonnes of soot could be released into the atmosphere — similar to the Mount Tambora eruption over 200 years ago.

This would knock out Canada’s ability to feed itself. A quarter of the world’s population would starve — and that’s in a situation where farmers manage to save some livestock, according to the pre-print.

As the hypothetical conflicts climb in intensity, so too do the number of aerosols released into the atmosphere.

At 27 million tonnes of soot, a third of humanity starves; at 47 million tonnes, nearly half perish from a lack of food.

And in the event of a full-scale U.S.-Russia nuclear conflict, the 150 million tonnes of atmospheric soot would lead to a famine in which 80 per cent of the world dies within two years of the war.

In northern latitude countries like Canada, the United States, Russia, France and even China, a lack of food would wipe nearly all of the human populations from the face of the Earth.

“Even if this is low-probability that it's this bad, still these very small nuclear wars have a very large impact… And so then, the question is, should we have weapons that could destroy human civilization, and basically, all ecosystem that we care about?” said Harrison, before answering her own question.

“Like Carl Sagan says, this ‘is elementary planetary hygiene.’ We should not have weapons available that could destroy us. Like, it's a bad idea.”