A parade of hot weather has scorched much of Western Canada in recent weeks, melting dozens of temperature records and setting the conditions for a series of devastating wildfires across B.C. and Alberta.

Some climate scientists have said the unseasonably hot spring weather was made at least five times more likely due to human-caused climate change, and that a hot summer is likely coming next. That has prompted a group of experts to share practical advice on how to adapt to the heat long before it arrives.

Joanna Eyquem, managing director of climate-resilient infrastructure at the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation, said the recent series of hot spells across Western Canada may be making people feel anxious or even powerless. She said by giving individuals practical solutions, research has shown it helps them feel more in control.

“People are kind of conscious of decisions that they can make to lower their own emissions, but they're not really aware of what they can do to reduce climate risks to themselves and their own daily life,” said Eyquem.

“We’re trying to get adaptation down to the grassroots level, so that it's part of our daily life and how we make our decisions.”

Advice includes “no cost, low cost, and slightly more complex” DIY upgrades to detached homes, apartments and condos. Eyquem said they are designed to be accessible to as many people as possible — both renters and homeowners — so people can help themselves.

The heat guidance follows a compendium report released last year by Eyquem, detailing what cities, homeowners, landlords and tenants can do to adapt to a warming world and remain as comfortable as possible.

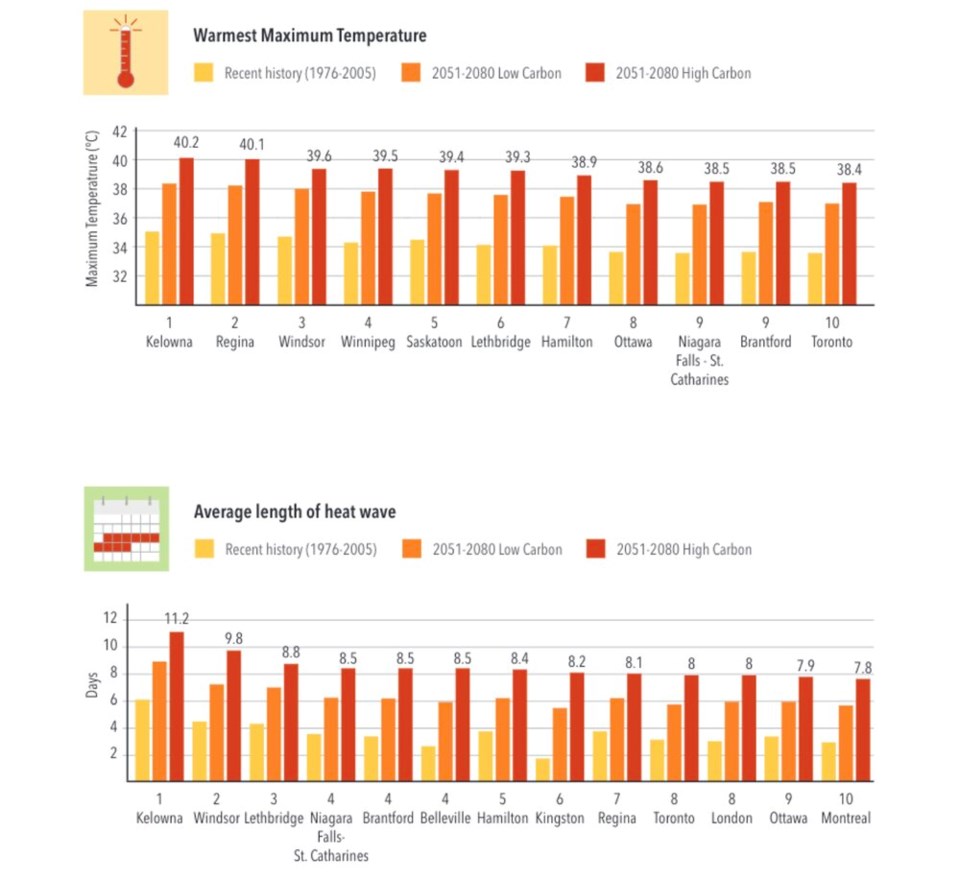

That report found many communities across B.C. are expected to fall in one of Canada's three “red zones,” where precipitous rises in temperature will sweep through prairie communities bordering the U.S., the north shore of Lake Erie through the St. Lawrence River Valley in Ontario and Quebec, and B.C.'s southern Interior.

In the last half of this century, Kelowna is likely to see the warmest maximum temperatures and longest heat waves of any major city in Canada. Smaller Interior communities like Kamloops, Penticton, Creston and Vernon are also expected to reach similar temperatures.

The Intact Centre had previously released similar guidance to protect against risk of flooding and wildfire. But this is the first time extreme heat — what Eyquem calls a “silent killer — is being targeted.

“The impacts of heat are death,” said Eyquem at the time.

She says cities like Vancouver provided input to help her craft the original report, and since releasing the practical guidance for residents, she has already had the cities of Calgary and Montreal step up to either craft their own versions or distribute it to residents.

The guidance released this week includes making a plan to check on vulnerable people during a heat wave, finding ways to shade your home with plants and trees, or blocking sun directly by installing blinds, heat-resistant curtains or window films.

In some cases, the advice is not universal and needs to be adapted to a community. For example, whereas you might consider planting a tree next to a home to benefit from its cooling effects in a place like Metro Vancouver, Eyquem says that could be a dangerous proposition in a fire-prone town in B.C.’s Okanagan Valley.

Eyquem said she’s looking at releasing practical and targeted advice for a combined disaster next, such as when extreme heat and wildfire smoke hit at the same time. She said the Intact Centre will also be targeting landlords, cities and other levels of government with how they can do their part.

'Punting real solutions down the road'

Other experts say focusing too much on what individuals should do to prepare themselves for the fallout from climate change can risk focusing on “band-aid” solutions.

You might be able to deflect some of the sunlight coming into a home, said Betsy Agar, director of the building program at the climate think tank the Pembina Institute, but what ultimately needs to happen is finding a way to holistically seal buildings, and get low-emissions heating and ventilation systems installed.

“There can be some concern that if we do these what we call 'low-hanging fruit,' we're actually punting the real solutions down the road,” Agar said.

"And in some ways, people might feel like they've solved the problem, when they really just kind of scratched the surface of what could and needs to be done.”

Agar says some of the most pressing upgrades should be targeted at the large number of Canadians living in low-rise buildings built decades ago without a warming world in mind.

“We think there's a priority of really preserving that kind of building,” she said. “They're actually often most affordable, but they also are the ones that kind of need the most work.”

In most Canadian cities, roughly 80 per cent of the buildings that will be standing in 2050 have already been built, says Agar. Considering the expected rise in intensity and frequency of heat waves, she says stop-gap DIY solutions aren’t going to keep people living in such buildings safe over the coming decades.

“I'd say anything that’s, you know, older than 20 to 25 years, is probably due for many of these deep retrofit measures,” she said.

One of the biggest problems standing in the way of deep retrofits is finding a way to pay for it. Some solutions in energy, heating and cooling have already come forward, such as government and BC Hydro rebates for heat pumps. But those often only apply to homeowners.

This week, the B.C. government put out a call for public input as it moves to update the provincial building code. But that code only applies to new buildings. Regulations to guide retrofits and adapt to climate change are still missing at the provincial level, though many cities — whose emissions are often dominated by buildings — have moved ahead on their own.

Until recently, many cities have prioritized lowering emissions. After the 2021 heat wave that hit B.C., killing hundreds of people, the calculation is being re-adjusted, Agar said.

“Do I have all the answers I know this is how we get it done? No. But what we know is that we need to have a combination of regulations,” said the building science engineer, pointing to mixture of loans, grants, subsidies and tax cuts as incentives so landlords upgrade their buildings.

“We have a public health issue. We need to expand our thinking about the critical role that housing plays in maintaining our public health.”