British Columbia’s most iconic ski resort is facing warming winters in a trend that could eventually threaten its existence, indicate decades of snowfall and temperature data.

The measurements, which stretch back to the 1970s, show long-term temperature and precipitation trends at Whistler's Roundhouse Lodge — an alpine hub of ski lifts, gondolas, restaurants and shops high up on the mountain where many visitors ski and snowboard.

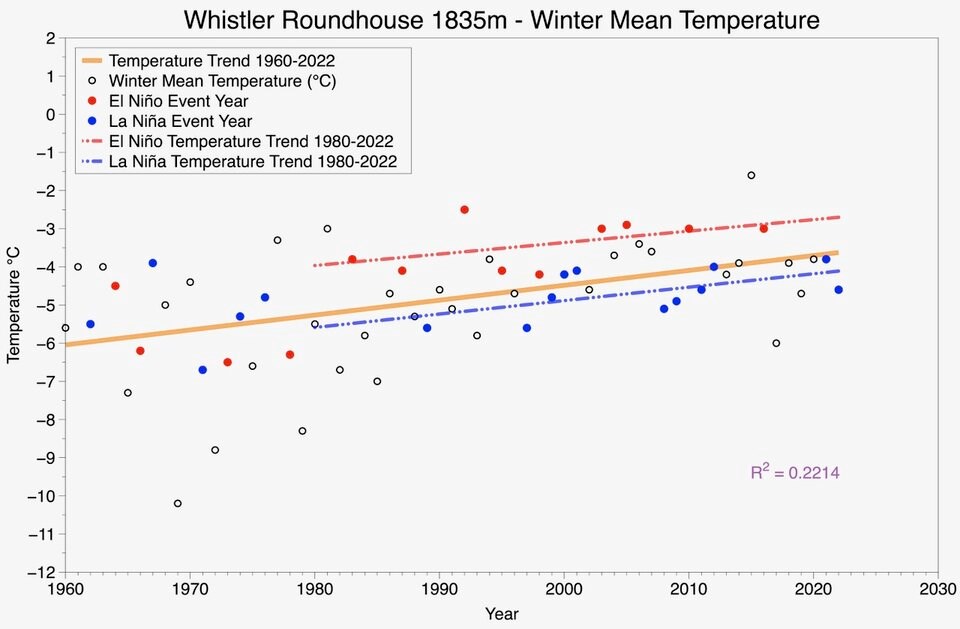

Michael Pidwirny, a climatologist at the University of British Columbia Okanagan, who recently analyzed the data, says there is a clear pattern: as human-caused climate change collides with El Niño-dominated winters, the warming and drying effects are getting worse.

“It’s adding a bit more heat all the time to the mid-latitudes,” Pidwirny said.

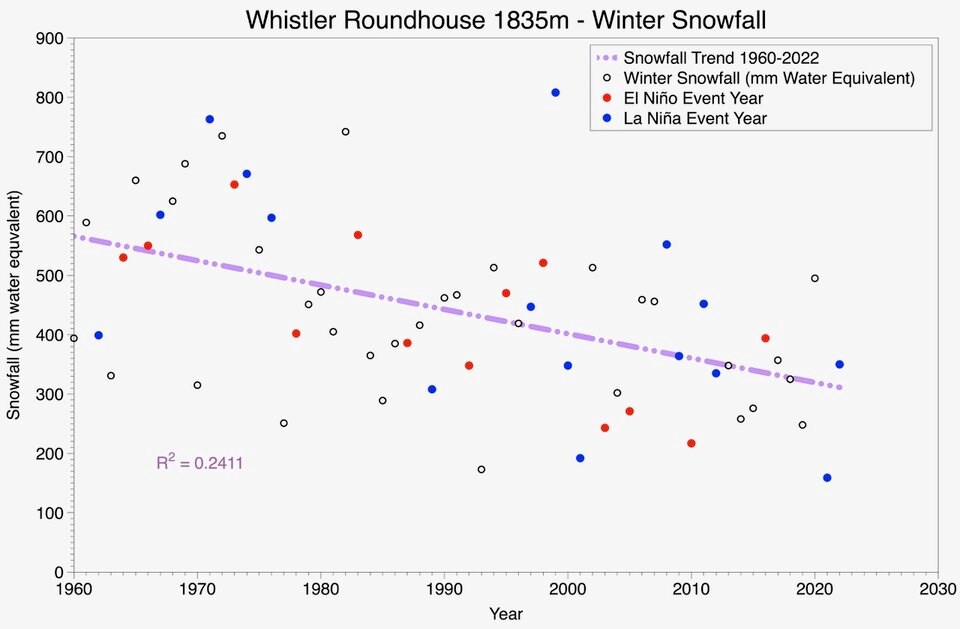

Average snowfall has also dropped, likely due to more precipitation falling as rain instead of snow, Pidwirny said.

As average winter temperatures go up, freezing levels are climbing, leading to more rain at higher elevations.

Over the coming decades, that trend is only expected to get worse.

Whistler ‘won’t be economical’

Climate models suggest that by 2085, half of winter precipitation falling on Whistler Village will come as rain, according to the UBCO researcher's analysis of ClimateBC models.

“The bottom of the resort is just going to have more years where there’s no snow at the bottom. You’re going to have to take the gondola up and down,” Pidwirny said.

That worries Pidwirny, as it could lead to massive bottlenecks and lineups that would throw the logistics of moving skiers around the resort into chaos.

“Whistler will not be a ski resort by 2085. It probably won’t be economical to run it as a ski resort by 2050,” he said.

As early as 2021, Whistler Blackcomb owner Vail Resorts told Glacier Media it was already seeing a higher variability in conditions, especially in the early season.

“We’re not preparing for more or less snowfall; we are preparing for more change,” then spokesperson Margory Elwell said.

At the time, Elwell said that the company had invested in more snow-making equipment and offered pass holders options to ski at other resorts when one had poor conditions. She added: “we’ve seen consistent snowfall at Whistler Blackcomb and this trend is expected to continue.”

But the 2023-24 season has been anything but “consistent,” and if Pidwirny’s analysis holds true, Whistler could face increasing pressure from climate-driven warming.

“This is probably the most important environmental catastrophes that humanity will ever face, and we just have our heads in the sand,” he said.

Like many ski hill operators, Vail Resorts has made efforts to expand its winter activities.

Sara Roston, communications director for Vail Resorts’ West Region, said the company takes the impacts of climate change “extremely seriously.”

The ski industry “used to be ruled by weather,” she said, but through its Epic Pass, the company has locked in revenue from 2.4 million guests across North America, Australia and Europe. Every year, that allows skiers and snowboarders (at least those with enough time and money) to travel to where the snow is, while giving Vail Resorts the funds to reinvest in snow-making equipment, said Roston.

Vail Resorts owns 37 resorts in North America, stretching from the Pacific Northwest to Lake Tahoe, to the Rocky Mountains and all the way to the Eastern Seaboard, noted Roston.

“For our North American Pass Holders, this means they have choice on where to visit, and as a company, our business is not dependent on the conditions in one region,” Roston wrote in an emailed statement.

Outside of the ski season, Whistler has greatly grown its mountain biking trails and other summer attractions.

But according to its 2023 Annual Meeting of Stockholders Proxy Statement, revenues and profits generated from mountain summer activities as well as golf peak season operations “are not nearly sufficient to off-set off-season losses from our other mountain and lodging operations. This impact could be exacerbated by climate change.”

Vail Resorts adds: “There can be no assurance that our resorts will receive seasonal snowfalls near their historical averages.”

Roston did not address questions over whether Whistler Blackcomb could sustain an economical business model in the latter half of the century.

This year's ski season among worst on record so far

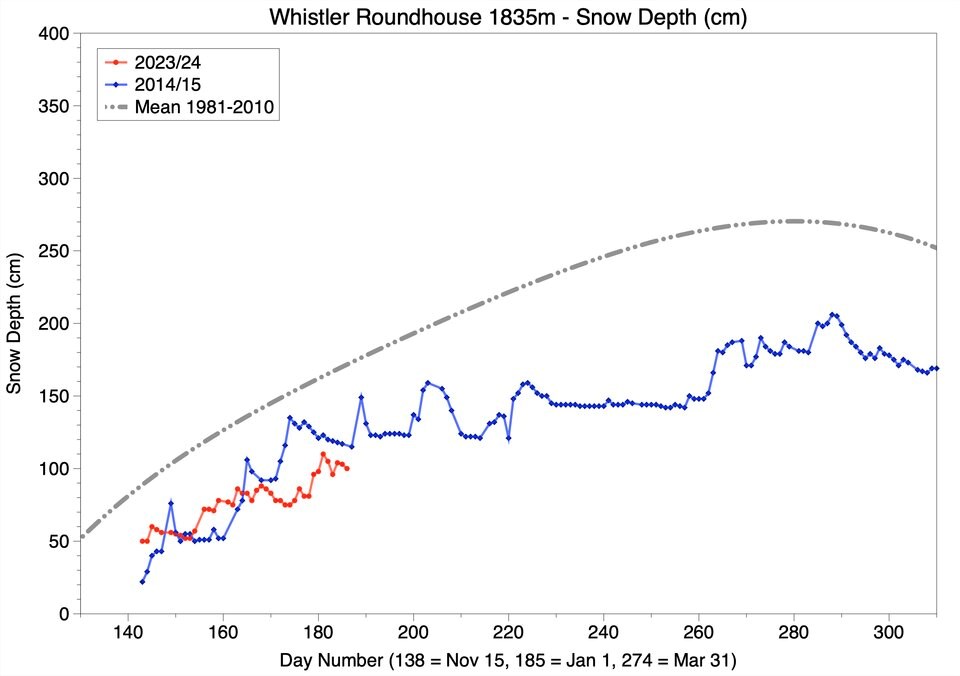

By Jan. 2, 2024, snow depth at Whistler’s Roundhouse station sat at 99 centimetres.

That’s about half the snow depth that existed at the same location on the same day in 2022, the last time B.C.’s coastal resorts saw an average season, says Pidwirny.

That week, the amount of accumulated snow at Whistler’s Roundhouse had even dipped below that of the 2014-15 ski season, among the worst on record. Over the coming days more than 100 centimetres fell on the resort, leading to long lineups last weekend and deep powder runs throughout last week.

Still, said Pidwirny — an avid skier who has long worked with resorts across the province — Whistler is “not going to catch up” this season.

He pointed to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center, which earlier this month released its long-range forecast for February.

Warm temperature anomalies are expected to cover nearly all B.C., while precipitation across the southwest of the province is predicted to be significantly below average, according to the forecast.

In other words, if December felt like a bad start to the ski season, February could be much worse. That leaves a small window of cold weather and snowfall over the coming weeks, said Pidwirny.

“For the next [two] weeks, I’d put money down we’re going to see snowfall,” he said.

“But after that, I wouldn’t.”