Coming to know

The discovery of unmarked burial sites in Kamloops is in a long line of opportunities for Canada to understand its history more fully. However, the tendency has been to diminish, deny and, wherever possible, actively forget.

This concept becomes apparent when examining how history is written and retold in Canada through commemorations, monuments or national holidays. Who is telling (controlling) the story? Who does it serve? Who does it include/exclude?

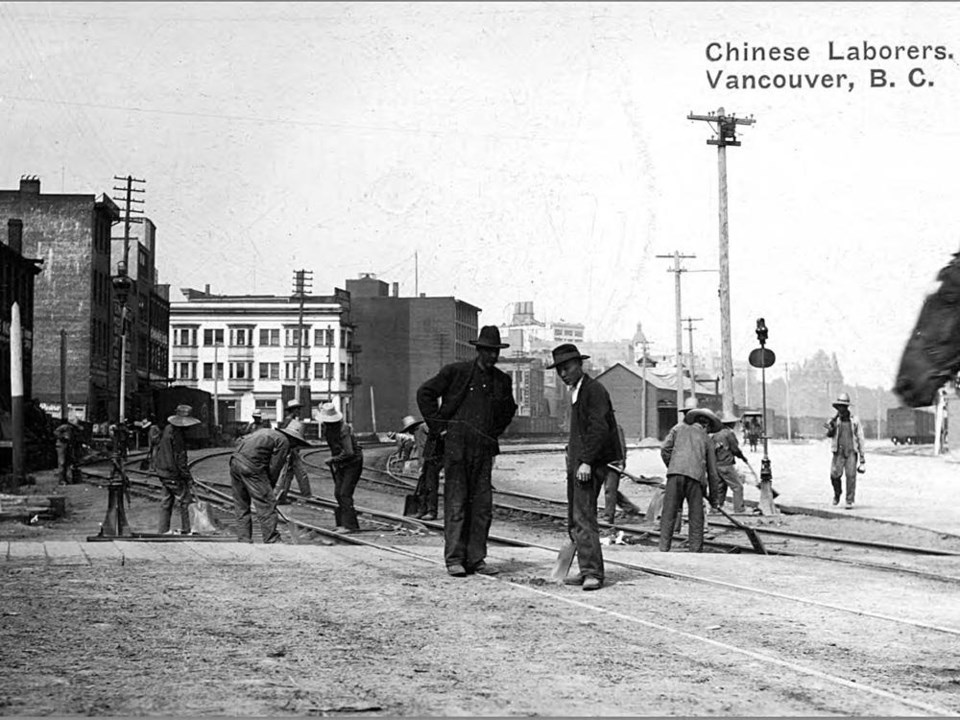

Canada Day, for instance, is also known as Humiliation Day. July 1, 1923, marks the date when the Chinese Exclusion Act became law. This legislation restricted all Chinese immigration to Canada and followed a list of increasing exclusionary measures. For those already living in Canada, the Department of Chinese Immigration and Colonization mandated that all Chinese register and carry photo identification to verify their compliance with the act, Canadian-born and naturalized Chinese included.

Chinese labour was exploitative and for economic gain. Once the railway was built, Chinese presence was merely a polluting source, a threat to the purity of the White Man’s Province.

A 1902 Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese Immigration characterized the Chinese as a “servile class.” Indeed, the Powell River Paper Company, hotel and several local households used Chinese servants. The commission determined the Chinese as “unfit for full citizenship” and “dangerous to the state.”

Why?

“Canada would be strengthened by exclusion of the Chinese race” who “depress wages” and “lower the standard of living.”

Anti-Asian racism is as loud and clear today as in the early 1900s. The proliferation of such as provoked by COVID-19 simply exposed a trope that has been here all along.

Multiculturalism is enthusiastically embraced by Canadians, which gives the impression of a cohesive, tolerant, welcoming nation. For whom?

Collective memory: Forgetting

There will always be different perspectives and voices, but which narratives would/should achieve dominance?

Forgetting is imperative to the ongoing colonial project.

For James Wertsch, Voices of Collective Remembering, remembering is a “mediated process in which specific technologies authorize certain acts of remembering while silencing others.” Technologies, in this sense, refer to public monuments, school textbooks, civic discourse, place names, etcetera.

We can find repeated patterns enacting settler-colonial dominance through memorialization, not only here but in every city and town across Canada.

The celebrated story tells of who belongs and who does not. It forms the backdrop that “validates” racism. A question commonly directed toward people with non-white features and skin tones is: Where are you from? (How could they be from [white] Canada?)

The colonial project is the story told, retold, deliberately remembered and sustained.

As historian Patrick Wolfe famously states: “Invasion is a structure, not an event.”

This is an ever-present reality for Indigenous people. Yet, it remains in silence for settlers until such a time as a dominant system gets challenged (as in name changing).

To unsettle the narrative, make visible those deliberately excluded, expose questions of “race,” gender and class, note exploitation and expropriation. Then, maybe amends can be made.

Exposure of what was “hidden” is an invitation

The issue of a name change exposes the broader problem identified by historian Timothy J. Stanley: the “collective remembering in Canada has failed to come to terms with the centrality of genocide, of racism, and of their ongoing effects in the process of making people and things ‘Canadian.’”

If this were acknowledged, there would be no “issue,” no resentment, no call for a referendum. The truth is strategically placed before reconciliation; without it, we continue to circle a repressive and unjust reality.

Kirsten Van’t Schip was born and raised in qathet. After many years away from the community, she returned to raise her three children. She holds a BA in anthropology and is currently completing a master of arts in heritage and social history.