The B.C. government has spent $2.667 billion in the past five years on mental-health and substance-abuse services.

That’s going to look cheap in a few years, judging by the recommendations from a committee that examined the response to the toxic drug and overdose crisis.

The theme of the 37 ideas advocated by the all-party committee shows up in the verbs used: Expand. Create. Fund and implement. Scale up. Increase.

In short, do everything that’s already underway and do still more, on an expedited emergency basis, on all fronts.

Although a provincial state of health emergency was declared in 2016 regarding the opioid crisis, the report says the pandemic emergency that developed later was dealt with on a more urgent basis.

The committee recommends taking the same approach to opioid deaths that was taken against COVID-19 — a full-on response that would go much further than the considerable lengths already taken.

Various experts, including Chief Coroner Lisa Lapointe, said the magnitude of the toxicity and overdose crisis demands a scaled-up response.

“Many pointed to how government and societies responded to the COVID-19 pandemic as an example of what is possible … and suggested that a similar response is warranted …”

MLAs agreed emphatically, saying “the committee was united in its belief that the tragic number of lives that continue to be lost … underscores the need for a scaled-up, emergency government response.”

Illicit drug abuse is the second-leading cause of years of potential life lost, while COVID-19 is ranked sixth.

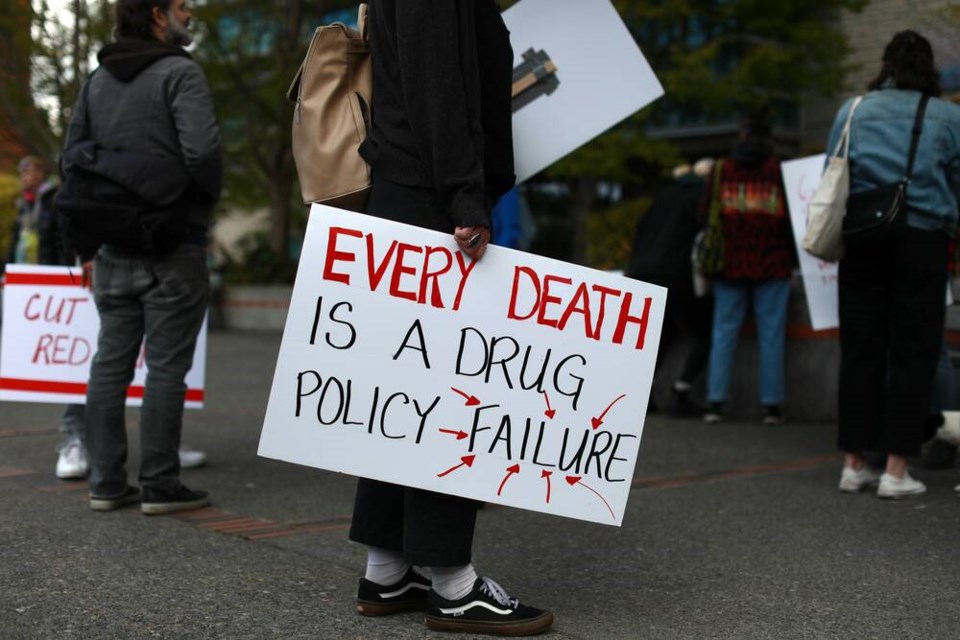

Six people are still dying of overdoses every day in B.C., but criticism of the current approach is relatively muted. The calls for more action and the view that there are critical gaps in care only implicitly acknowledge that not enough is being done.

The closest thing to outright criticism is in observations about public reporting.

The only constant reporting that can be used to evaluate the government’s response is the coroner’s monthly illicit drug deaths report. MLAs want more regular updates on all fronts made public, because the intermittent announcements about new initiatives may not receive attention. “There is a need for more public reporting from both public health and government officials.”

It said accountability needs to be improved by defining and reporting on goals, metrics and timelines.

The committee also wants health authorities dealt more into the action. They should be held accountable for rapidly expanding services. MLAs were struck by how rarely they come together to discuss the opioid crisis. They said clearer expectations should be set for the authorities and regular reporting on progress should be mandated.

There was also discussion about the need for more clarity on whether the Health Ministry or the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions is ultimately responsible for responding. The latter is a shell ministry created by the NDP five years ago. It develops programs but is not directly responsible for them and runs on a relatively modest $20-million budget.

Ten thousand people have died in the six years since the emergency was declared and illicit drug toxicity is the leading cause of unnatural death in B.C., more than homicides, car crashes, drowning and fires combined.

MLAs dwelt on an earlier finding that prompted deep concern. It’s about how close deceased overdose victims actually were to help.

Almost three-quarters of them had a visit with a health professional less than three months before their death. Almost a third had 10 or more visits in the months before their death. And 44 per cent of the dead got a social assistance payment within a month of their death.

Those were all chances to intervene and connect with users — chances that were lost or that failed. The committee highlighted the “warm hand-off” approach, where any service provider would be expected to ensure someone at risk is personally connected to another provider who can help.

Involuntary care has been an on-and-off controversy in recent years.

The NDP was forced to withdraw legislation that would have provided that option for young people because of controversy. Premier designate David Eby raised the issue again this year.

The committee referred to people who argued for and against that option during its hearings. But it took no position.

MLAs call for more action, A4