Ticks can’t fly. But they can do a little dance.

It’s not something most British Columbians likely think about on a regular basis. For Stefan Iwasawa, however, the mechanics of the blood-sucking, pathogen-carrying insects have become a daily calculation.

Since he first tracked ticks in the tropical climes of Belize almost 15 years ago, Iwasawa’s passion for the little critters has escalated to a reputation — at the BC Centre for Disease Control, he's known as “the tick guy.”

“I guess I’m a tick whisperer,” he said from his home in Nanaimo, B.C.

Part of the job means doing active surveillance for an insect whose range is projected to rapidly shift as B.C. becomes wetter and hotter because of a shifting climate.

Between now and next fall, Isawawa’s tick surveillance plans will take him up the east coast of Vancouver Island — to Victoria, Salt Spring Island, Nanaimo, Parksville, Comox and Campbell River — and around the Lower Mainland in Surrey, Belcarra, the Capilano River, Pacific Spirit Park and Bowen Island.

It starts decidedly low-tech, with a trip down to Home Depot where he picks up a white painter’s suit, some tape, dowelling and a low-grade one-by-one metre patch of cloth known as ‘diaper flannel.’

Choosing a location to go ‘ticking,’ as he calls it, requires finding places where human and insect presence overlap — then waiting for the right conditions. A wet, muddy day is not the time to hunt ticks.

Sometimes Iwasawa will contact a local tourism board. Other times he’ll look up sightings on a new public tick app.

Local parks, trails, anywhere with a lot of human and dog traffic are safe bets.

Donning the painter suit, Iwasawa duct tapes his pant legs to his shoes and strings the dowelling to one end of the flannel square. He then drags the contraption behind him, mimicking the hindquarters of a dog or calf of a hiker.

If there’s taller foliage along the trail, Iwasawa will make a flag out of the material, dusting the bushes as he goes by.

“It’s just a slow, meandering walk,” he said. “It’s a lot of fun.”

Everything is calculated to catch a tick when it’s ‘questing.’ Picture the insect throwing up its front legs into the air like the "Y" part of the "YMCA" dance moves.

“It’s a ‘pick me’ situation, like a toddler who wants to get picked up,” he said. “They'll latch on to little people or they’ll latch on to your animals.”

Once sweeping an area, Iwasawa rolls up the flannel, scanning it from side to side and tweezing off any ticks into a vial. They will get tested at a BC Centre for Disease Control lab later for Lyme disease or another pathogen. It’s a process that happens roughly 900 times a year in the province.

Ten ticks in four hours was the researcher's biggest haul — except for that time he caught an egg clutch of 30 larvae, “a big day.”

But as Iwasawa put it, “That could change.”

Lyme disease on the rise

The most commonly reported vector-borne disease in Canada, since 2009, Lyme disease has seen a nearly 20-fold spike in reported cases across the country, according to data from the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Much of that increase has been driven by surging cases in Eastern Canada, where climate change has already expanded the range of many tick species — the primary vector for the spiral-shaped Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria that causes the disease.

“We’re seeing more and more cases of Lyme disease being reported further and further west... encroaching more towards Manitoba,” said Erin Fraser, a BCCDC public health veterinarian and a clinical assistant professor at UBC’s School of Population and Public Health.

“We want to keep a really close eye on that.”

In B.C., however, reported cases of Lyme disease have remained relatively steady over the past decade, according to the BCCDC.

Those cases that have been reported have been driven by the Western black-legged tick (Ixodes pacificus) — a species ranging south to California and carrying the bacteria causing Lyme disease at a rate of about one in 100 insects, says Iwasawa.

Starved, these ticks are rarely bigger than a sesame seed, but once engorged on a blood-meal, they can balloon to the width of a fingernail.

In British Columbia, Western black-legged ticks usually pick up the disease when they feed on deer, mice, squirrels or chipmunks — all known reservoirs for the bacteria.

But a dog, farm animal or human can easily fill in for a meal. One bite from an infected tick and a debilitating disease can follow.

What is Lyme disease?

Once the B. burgdorferi bacteria passes into the human bloodstream, symptoms of Lyme disease can appear within hours, days or even weeks.

They typically include a headache, fever, fatigue and a skin rash that looks like a bull’s eye. Quick diagnoses and treatment with antibiotics can kill an infection within a few weeks. But if left untreated, long-term symptoms can complicate every aspect of life, leading to severe headaches, neck stiffness, severe arthritis and intermittent pain in joints, muscles and tendons.

In some cases, facial palsy, where muscle drops on one or both sides of the face, can occur. Others experience heart palpitations known as Lyme carditis, spells of dizziness and shortness of breath, as well as shooting pains and tingling sensations in the hands or feet.

Inflammation of the brain or spinal cord has also been documented.

Many of those symptoms have been known to persist even in patients who have sought timely treatment. Much like long-COVID, Lyme disease support groups with tens of thousands of people have sprung up on social media platforms, with many claiming decades of chronic illness.

Yet according to the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, much remains unknown.

“The state of the science relating to persistent symptoms associated with Lyme disease is limited, emerging, and unsettled,” notes the CDC.

Ticks on the move

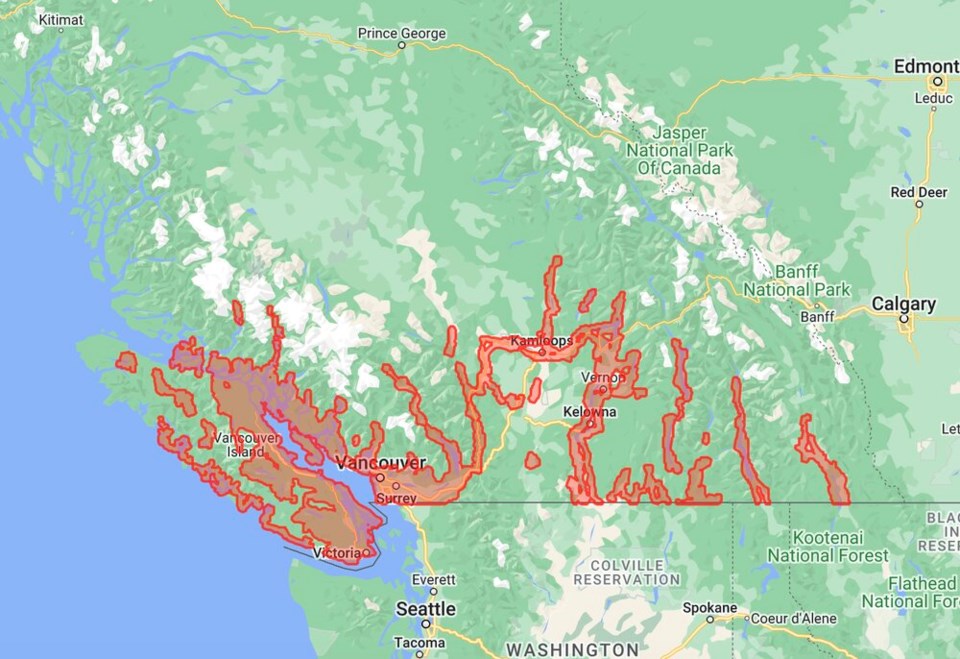

The highest risk areas for Lyme disease in B.C. also happen to overlap with the province's biggest population centres.

They include the Lower Mainland, southern Vancouver Island and Gulf Islands, and to a lesser extent, some of the valleys of the southern Interior, according to the BCCDC.

Across the continent there are some startling differences.

Unlike some of its counterparts in Eastern Canada and the United States, the western black-legged tick transmits Lyme disease at a curiously low rate.

Some scientists have attributed this to its tendency to feed on three species of lizard, which are thought to somehow neutralize the disease-causing bacteria, says Fraser.

“There’s early evidence,” she said. “There’s something in the lizard’s blood that sort of immobilizes or changes the pathogen to some degree. But there's lots of things that we don't understand about the life cycle and transmission dynamics for disease.”

A decade ago, now provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry penned an article with the title “Lyme disease in British Columbia: Are we really missing an epidemic?”

She concluded that there’s no evidence B.C.’s surveillance of the disease was flagging. Instead, she wrote that more research was needed to understand chronic Lyme disease and health authorities should continue to monitor the situation.

That situation could change in the coming years as ticks move from North America’s east to west.

One of the uncertainties in the transmission of Lyme disease in B.C. comes from projected shifts in temperature and rainfall, which could alter animal habitats.

At the same time, other tick species are on the move. Fraser and Iwasawa point to ongoing research they’re involved in to track the effects of climate change on the spread of several pathogen-bearing ticks, such as the black-legged tick (not to be confused with the western species) which has so far has been found through passive surveillance in every province but B.C.

Some tick species could pose a significant risk to animals. First detected in New Jersey in 2017, the invasive Asian longhorn tick can reproduce asexually, laying up to 2,000 eggs at a time without a mate.

Clinging to a cow, such a huge volume of ticks can effectively bleed the animal to death, says Fraser. And according to one 2020 study Fraser points to, coastal B.C. could become a prime location for the invasive tick to expand its range in the coming years.

Could climate-driven tick migration force some British Columbians to give up meat?

Some of the greatest anxiety comes from the so-called lone star tick, an American species that carries a number of pathogens and whose saliva is thought to trigger an immune response to the alpha-gal carbohydrate found in red meat. A bite from a lone star tick has been linked to long-term meat allergies.

One 2019 study found under shifting climate scenarios, the lone star tick could extend its range up the west coast of North America from California to southwestern British Columbia, including the Lower Mainland, eastern and southern Vancouver Island and a portion of Haida Gwaii.

Warning of “massive range under-estimation,” the researchers found the lone star tick’s arrival in states like Minnesota already show a north and westward shift — a prelude to what could come under both low- and high-emissions scenarios.

”There are so many different signals that we're seeing here in North America and elsewhere,” said Fraser.

”Ticks are on the move.”

'Like Instagram for ticks'

As one of only a handful of ‘tickers’ in B.C., Iwasawa and his colleagues can only catch so many blood-sucking insects.

He says understanding how climate change is impacting the spread of tick-borne pathogens comes down to an avid public ready to take on part-time roles as citizen scientists.

That often starts with an explanation.

“When you're in the field, you get a lot of people asking why exactly you're walking around in a white suit: ‘Is it a crime scene?’ or ‘Are you trying to fly a kite?’ You know, ‘What is that guy doing?’” he said.

The job doesn’t come without risks, and not only from the insects. One time ticking in Qualicum, a terrified dog walker called the RCMP on him, thinking he had murdered someone. When he returned to the parking lot, the police officers had boxed his car in and approached him with their hands near their weapons.

“We've had reports of somebody burying bodies in the forest,” they told him.

“Nope,” Iwasawa remembers saying, handing them a pamphlet on Lyme disease. “Just collecting ticks.”

More often than not, the strange looks are a chance to strike up a conversation, he says.

Sometimes Iwasawa tells people to throw hiking clothes into the dryer on high heat, shower and check for ticks after coming out of the bush, or to tuck their pant legs into their socks before they go out.

“There are ticks out there, so might as well take good steps now before something should happen,” he said.

Increasingly, those conversations are happening online.

In 2021, a federal team of researchers developed an app where Canadians can upload photos of ticks they find. When a photo gets posted, expert technicians identify the species and send back information on whether they should keep the tick in the freezer, monitor themselves for symptoms, or seek medical attention.

“It’s like Instagram for ticks,” said Fraser.

Soft-launched last summer, etick.ca is being ramped up this spring and doubles as a resource to understand risk to tick-borne pathogens as people travel across the country.

So far, B.C. residents have posted over 420 sightings, more than many other western provinces but a fraction of what’s been reported in southern Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia.

“That’s three times what we had last year,” said Fraser, still impressed, “and it’s only the end of May.”

Part of that is likely due to education, a promising sign for a preventable disease, says the researcher.

“We really don't want people to be panicked about this,” Fraser said.

“Just knowing the signs, monitoring for ticks [and] seeking health care as symptoms develop as soon as possible. It’s very treatable.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story stated ticks can't fly but they can jump. This is not accurate. Ticks, in fact, throw their arms in the air in a questing pose and hope to grab on to something. They do not bounce through the air under their own propulsion and can only fly when attached to a bird.

-05-18_at_35540_pm.jpg;w=960)