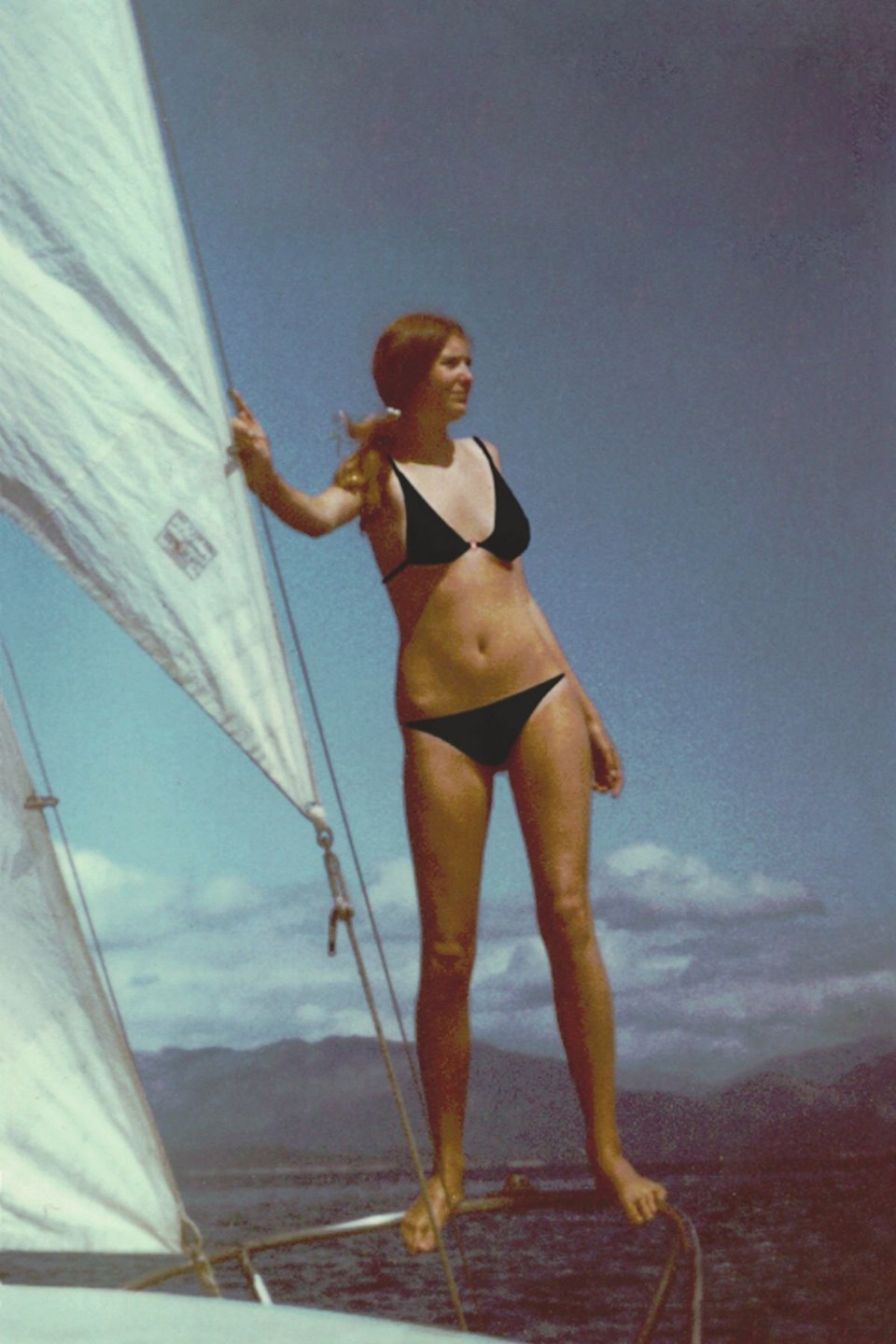

Chapter three recap: After a few years of sailing their own boat up and down the Salish Sea, 21-year-old Linda Syms and her boyfriend Wayne Lewis agreed to join their friend’s sailing adventure to Hawaii. It was the fall of 1974, and the couple only had $12 between them and no way to get home.

In Hawaii, they met a BC family who was abandoning its round-the-world sailing trip to fly home. Linda and Wayne offered to sail the family’s sailboat back to Canada. To help get back before the storms set in, they rounded up two more crew members: Norm, an able-bodied sailor, and Lenny, an out-of-it surfer kid who Linda found hanging around the dock.

On October 17, 1974, the journey home began. At dawn’s light, the crew was up, eager and excited. Wayne fired up the sailboat’s rumbling diesel engine. They untied the boat and shoved off with shouts of delight in the warm tropical breeze.

Wayne eased the gearshift into the forward position to guide the large sailboat out of the harbour and…the gear shift broke off in his hand. The engine coughed and died. They were adrift and hadn’t even left the harbour.

Suddenly that pleasant breeze was blowing them into the shore. To the rescue came their friend, Gary Gagne, the man who sailed them down to Hawaii. He too was leaving that day, headed south to Guam. He managed to bring his boat alongside and steer them into the open ocean where they could safely catch the wind and point the bow north by northeast for Canada.

On the second day, when they attempted to start the motor, it wouldn’t turn over. To their dismay, the batteries were almost completely dead, only providing enough power to light their compass at night. On day three, they hit their first chaotic gale, which is when they made another horrible discovery: the boat wasn’t watertight.

“The one thing I remember was lying in the forward berth and the hatch above me leaked so badly that with every wave there would be a deluge of water right onto my head,” said Linda years later, with a chuckle.

Since the batteries were dead, that meant the automatic bilge pump wasn’t working, so the bottom of the boat was filling up with water and had to be manually pumped out constantly.

They woke up on day four soaking wet and nauseous, but it wasn’t from sea sickness. Choking diesel fumes had inexplicably filled the cabin. Even though the storm had abated, the pumping didn’t seem to lessen the water that was sloshing around the floor of the cabin.

By day five, diesel fumes still permeated the cabin and water was ankle deep. Wayne eventually tore up the floorboards to reveal three thousand-litre rubber bags. One held the diesel fuel, one held the fresh drinking water for the voyage, and one was the holding tank for their toilet waste.

To their collective disgust, they realized the gale had dislodged the bags from their foam mounts. They had rubbed up against the rough concrete hull of the inside of the boat and two of the bags had split their seams: the diesel fuel and the fresh water. That meant they had one 20-litre jug of fresh water between the four of them for a month at sea, and 300 cans of Schlitz beer.

You could say they were up Schlitz creek. At least the sewage tank hadn’t burst.

Wayne had once promised Linda that their life together would never be boring, but even this situation was too much for him. He had grown up on boats and served in the navy. He recognized the situation for what it was: they were in the middle of the ocean aboard a life-threatening lemon.

The batteries were so dead they couldn’t use the VHF radio to send out a mayday should they need to, nor did the running lights work, vital for alerting freighters of their presence at night. And the boat kept leaking, not only from the top hatches and windows, but from the hull as well.

The propane fridge wasn’t functioning properly, thanks to the rolling sea, which meant their fresh food was spoiling before they could eat it. Not even the toilet was working properly; it was overflowing and creating a horrible mess.

Determined decision

Wayne decided they had to turn back to Hawaii immediately before risking their lives any further. Possibly summoning the Norwegian within her, 21-year-old Linda insisted they keep sailing. She figured it was bound to rain – fresh water from the sky - and hey, they were on a sailboat, they didn’t need fuel or gears. And “who would answer a mayday call way out here anyway?”

“Let’s keep going,” urged Linda.

Somehow, she convinced the other two crew members. Against Wayne’s better judgment, they kept going.

There were pleasant times. Once, Lenny reeled in a large bright green mahi-mahi, which Linda still claims is the best fish she ever tasted. Other times, dolphins and albatross would visit, the sun would come out and they could dry off and relax.

Every night at happy hour, they each cracked open a beer or two, which also perked up the mood. But the skies remained clear, with no rain clouds in sight.

By Day 13, they were down to their last two litres of drinking water. That morning, a storm whipped up and turned the ocean into a frothing mess, but still no rain. Spray swept the length of the boat and the bow plunged under green water with every massive wave.

Inside was a complete disaster, with food, dishes, sodden clothing and gear flying everywhere. Water sloshed up to their ankles. And then, finally, black clouds rolled in overhead. It poured.

The crew madly scrambled onto the deck, braving the wicked storm to catch the fresh water running off the sails, but Wayne shouted that they had to be patient. The sails were saturated with salt water from the waves. They had to wait for the rain to rinse the sails before they could catch the water.

“We let the rain wash off any salt spray that was on the sails, and then we’d have buckets and frying pans and the kettle, anything we could collect water in,” explained Linda. “So we waited, and the rain water was pouring off the sails. We filled up a pot and drank from it, but it was too salty. The air was permeated with salt crystals so as the rain came down it collected salt.”

The water never purified.

The harsh reality of the phenomenon called salt water rain was the first time Linda became scared. The rule of threes state that you can’t survive longer than three weeks without food, three minutes without air, and three days without fresh water.

To add to the calamity, Wayne’s concerns about Lenny were becoming validated. To keep the boat constantly moving north by northeast toward Canada, they each took shifts at the tiller around the clock. Unfortunately, Lenny couldn’t stay on course and he couldn’t keep the sails from backfilling, a loud calamitous flapping that all could hear below deck.

Wayne and Lenny clashed from the start, and Lenny began to act more and more erratically. One day in heavy seas, Lenny spotted a glass ball, a Japanese fishing float that had gone astray. He considered the item to be such a treasure that he reached over to try and grab it but missed.

Wayne shouted for him to leave it. Instead, Lenny shocked the rest of the crew by leaping overboard, swimming madly after the ball, without a safety line, and without a life jacket, into the rolling grey swells of the Pacific Ocean.

What happened next? You’ll read about that in the next chapter of Wild Pick: The life and adventures of Linda Syms, oyster farmer of Desolation Sound.

Grant Lawrence is the author of the new book Return to Solitude, and a radio personality who considers Powell River and Desolation Sound his second home. Wild Pick originally aired as a radio series and podcast based on Linda Syms’ two books: Salt Water Rain and Shell Games. Both are for sale at Pollen Sweaters in Lund, and Powell River Outdoors and Marine Traders in Powell River.