We arrived in Ledegem just as church was letting out. It was 2006. I scanned the crowd for someone who could have lived in the village for more than 60 years and settled on an elderly gentleman.

“Excuse me sir!”

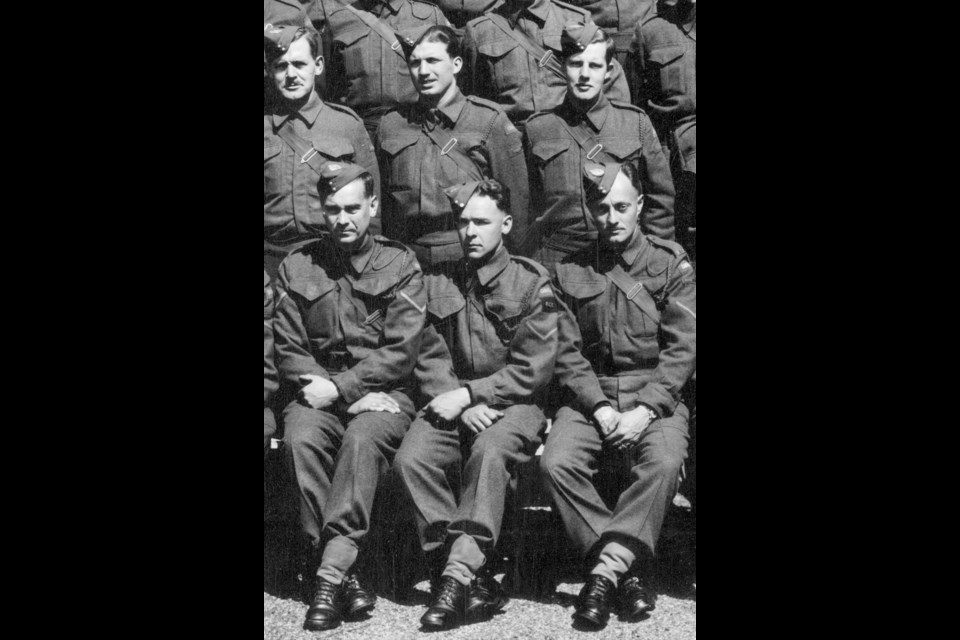

I held up a small black and white photo.

“Do you know who this is?”

The man looked blank and my hope evaporated. It had been a bit of a long shot after all.

My husband Arthur Arnold took up the role of translator and repeated my sentence in Dutch, which is similar to Flemish, the local language in this region of Belgium. The man smiled and took the photo – a picture of a small blond girl about three or four years of age with sparkling eyes, standing next to a soldier. On the back was scrawled “Anita, Ledegem.”

“I think I do know who this is!” he said, “but hmmm, I don’t know where she lives. Try down there at the butcher.”

Our timing was good, Belgian shops stay open until noon on Sunday, so I politely joined the queue at the butcher counter, ready to wait my turn. But Arthur, in the more direct Dutch style, took the floor and waved the photo.

“Excuse me!” he announced. “Do any of you know an Anita?”

“I do,” said a man. “Her auntie lives on this very street – ask at the pub.”

A few doors down, the bartender took the picture from me.

“Her auntie lives just next door,” he said. “Knock there and she’ll tell you where to go.”

Auntie didn’t answer her door, but the neighbour gave instructions and in a few minutes we were ringing a doorbell labelled Anita and Michel. Michel opened the door.

“Goede morgen,” said my translator, and he handed over the photo. “We’re looking for this girl.”

The man’s eyes widened.

“Anita! Come here,” he called, not taking his eyes from the image.

A petite woman looking young for her years, with wild, short blond hair, arrived at the door. She took the photo, confusion clouding her bright blue eyes.

“This is Kim Stokes,” Arthur said, pointing to me, “and this,” he pointed to the soldier, “is Art Stokes, Kim’s grandfather. We think he stayed with your family in 1945.”

“How is this possible?” asked Anita, pausing for a moment, staring at the photo. “This was taken more than 60 years ago. You must come in.”

Michel settled us on the sunny patio, while Anita poured us a late Sunday morning beer in the true Belgian style, and started to tell us about Ledegem during the war.

“When the Canadians arrived at the beginning of March, every villager with a spare bed had to offer it up,” she said.

My interpreter did a stellar job keeping up with the story.

“We lived over our shop on the main street,” continued Anita. “My father filled the attic with mattresses, and at least 20 soldiers stayed with us. I had such fun!

“I was like the little sister – they tossed me around, throwing me from one soldier to the next - I think I never touched the ground!”

There was that sparkle again. After a couple of hours of regaling and reminiscing, she asked: “Can you come back tomorrow? I’d like you to meet my auntie, she’ll remember.”

Village buzzes with stories

My grandfather, or rather, my Pop, survived the war. Upon his return to Canada, he moved his family of three to Quesnel, BC, where he opened a garage with another soldier from his squadron, Robbie.

Early in the 1970s my grandparents followed our family to Powell River, where Pop worked as a mechanic for the city. He loved the outdoors - fishing and camping - and he loved me, his only granddaughter. These are the things a girl knows about her grandfather.

He died when I was 16. I knew he had been a soldier, but he didn’t talk about it, so neither did we. The small photo was the only evidence I had of Pop’s war years.

When we returned to Ledegem the following day, the house was full of villagers buzzing with stories of the Canadians. Auntie was there, too. She remembered Art, and his friend Robbie.

“Oh, they were a handsome lot,” she blushed.

Auntie had been 17 at the time. I asked many questions and learned that the Canadians spent three weeks in the area, preparing to join the liberation push through the Netherlands. On March 24, they packed up and departed.

“Let me show you where your grandfather stayed,” offered Michel; it was near the butcher shop. “It’s being renovated, so it doesn’t look quite the same, but now you can look right into the attic. See, up there, that’s where they all slept.”

I stood still for a few minutes, knowing Pop had been exactly here, and then I picked up a piece of broken brick and tucked it away in my pocket.

Last year (2019), Dutch liberation commemorations flowed through the Netherlands like the tide coming in. Each evening, the Dutch news reported the Allied front position as if it was the day’s news, giving life to the 75-year-old timeline. Maastricht, in the south, was the first city to be liberated, September 14, 1944.

Our village, 20 kilometres to the north, took another four days, and so it flowed northward. The ongoing commemorations reminded me that I still didn’t know very much about what my grandfather actually did during the war.

“What do you know?” I asked my dad, who had been too young to remember his father leaving for the war, and six years old when he returned.

“He was a mechanic,” said Dad, “with the Royal Canadian Engineers, the 4th Field Park Squadron attached to the 5th Canadian Army.”

He handed me four loose-leaf pages, rough handwritten notes, with some dates, places and events.

September 1941 - Petawawa; November 8th, 1941 – Halifax – boarded Orensay, 13th sail for England; November 23rd, 1941 - Aldershot, Salamanca barracks; February 6th, 1942 – promoted to Corporal; October 26th, 1943 – board US troopship John Ericson at Liverpool; November 6th, 1943 – air raid by torpedo bombers, 2 ships sunk, 2 bombers shot down; November 8th, 1943 – dock at Naples; November 30th, 1943 – arrive at front to support 8th Army; February 5th, 1944 – caught in artillery barrage; May 21st, 1944 – Gustav Line; May 24th, 1944 - Hitler Line; September 15th, 1944 – Ernie killed (Ernie was his childhood friend); February 14th, 1945 - Florence; March 1st, 1945 – Ledegem.

The pages then tracked him through a few Dutch cities, Nijmegen, Arnhem, Barneveld, Heerenveen and finally to Groningen on April 23, 1945. The last entry: July 28th, 1945 - left Groningen for home.

It takes fewer than four hours to drive from our home in the south of the Netherlands to Groningen in the north. We called our friends who live in the city centre.

“Come,” they said. “We’ll show you around.”

Search provides peek through time

Late that evening, we all walked through the ancient city speaking in hushed tones as we wound our way along pretty canals and narrow stone streets toward the Grote Markt, the main market square where the Battle of Groningen had taken place April 14 to 18, 1945. According to my pages, Pop had arrived a couple of days after the battle. I imagined him getting to work fixing broken tanks and trucks.

“I wonder if I am walking in my grandfather’s footsteps?” I whispered, struck with the sense that I was the first member of the family to be here in 75 years.

We visited the quirky Victory Museum in a nearby village, a bizarre private collection of memorabilia dedicated to the Canadian liberation of the Netherlands.

An attendant unlocked the glass display cases and let me rummage through the shelves. I flipped through books and scanned the crowded shelves looking for – what? I wasn’t really sure. Then I spotted a framed crest with the title: 4th Canadian Field Park Squadron 1940-1945.

The crest was surrounded by the names of the places I found in my pages of notes: Hitler Line, Gustav Line, Arnhem, Barneveld. Another confirmation of Pop’s presence here.

Back home, I joined Mark Zuehlke’s Canadian Battle Series Group on Facebook.

“It’s really hard to find information,” I wrote.

They put me in touch with Tony at the Royal Canadian Engineer Museum. Tony graciously forgave my ignorance with all things military and gave me a few leads, even describing for me what Pop would have been doing during the war.

“I suspect he maintained the heavy vehicles such as bridge layers and heavy transport that the Royal Canadian Engineers would have utilized [...] while on the advance with the rest of the formation,” he told me.

He sent me to the Canadian Library Archives, where I found microfilm of war diaries and links to service records. But, because my grandfather survived the war, his records are not available.

And then, one morning a few days later, my Facebook notification was blinking. No message, just a website address from someone who’d seen my post. And there it was: War Diary 4th Field Park Squadron RCE, Major LG MacDonald.

The first entry is this: March 2nd, 1945. “Left CAMBRAI at 0900 hrs and arrived at our final destination for the entire journey, LEDEGEM, at 1520 hrs. Distance, 60 miles. Nearly the whole Sqn is now in excellent billets, and there’s no escape from the hospitality of Ledegem. Oppressive supplementary suppers of milk soup, potatoes and sausage, coffee and bread must be eaten by all. Every second house is a model beer parlour so there is beer in plenty.”

I smiled; I knew that hospitality. I read all 92 entries in one sitting. By the last entry, I knew I had found what I had been searching for - a little bit of insight into my grandfather’s life as a soldier - a small window that I could peek through that would take me back in time.

Would he ever have thought that what he did was important enough that his family would want to know about the details 75 years later? That I would search for, and find his footsteps to honour his memory? I hope so.

Lest we forget.

Kim Stokes grew up in Powell River. For the past 15 years, she and her husband Arthur Arnold have split their time between Powell River and The Netherlands. This article was originally published on Stokes’ blog, Waking Up on the Roof (wakingupontheroof.com) in November 2020.