COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. (AP) — As Colorado becomes the second state to legalize psychedelic therapy this week, a clash is playing out in Colorado Springs, where conservative leaders are restricting the treatment over objections from some of the city's 90,000 veterans, who've become flagbearers for psychedelic therapy to treat post-traumatic stress disorder.

Colorado residents voted to legalize the therapeutic use of psilocybin, the chemical compound found in psychedelic mushrooms, in a 2022 ballot measure, launching two years of rulemaking before it could be used to treat conditions such as depression and PTSD.

This week, companies and people will be able to apply for licenses to administer the mind-altering drug, though treatment will likely not be available for some months as applications are processed.

Colorado joined Oregon in legalizing psilocybin therapy, though the drug remains illegal in most other states and federally. Over the last year, a growing number of Oregon cities have voted to ban psilocybin. While Colorado metros cannot ban the treatment under state law, several conservative cities have worked to preemptively restrict the so-called “healing centers.”

At a city council meeting in Colorado Springs this month, members were set to vote on extending the state prohibition on healing centers from 1,000 feet to 1 mile from certain locations, such as schools. From the lectern, veterans implored them not to.

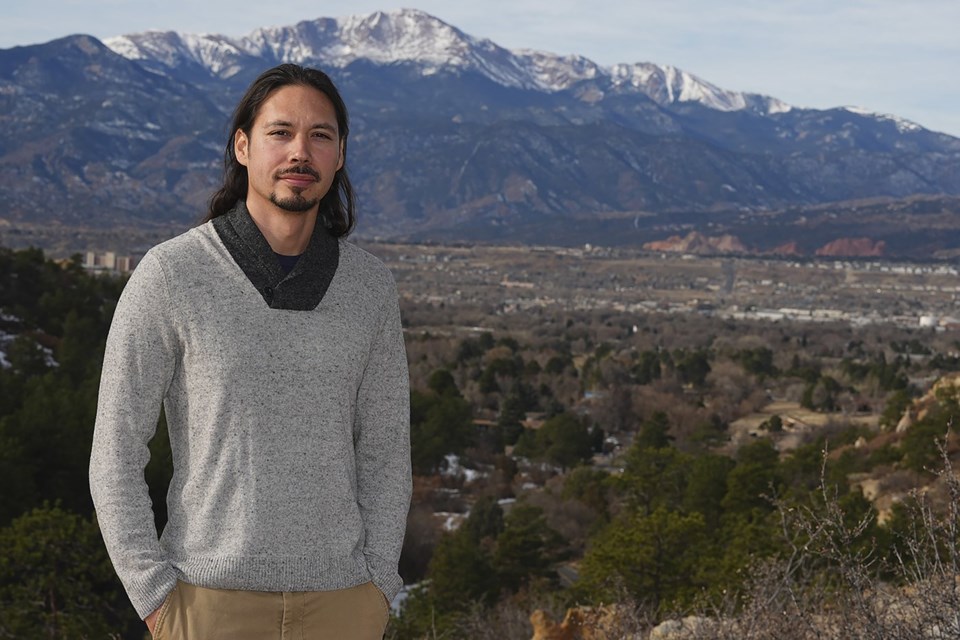

“We have an opportunity to support veterans, and it’s a really easy one to say ‘Yes’ to,” said Lane Belone, a special forces veteran who said he's benefited from his own psychedelic experiences. Belone argued that the restrictions effectively limit the number of centers and would mean longer waiting lists for the treatment.

Veterans have pulled in some conservative support for psychedelic therapy — managing to set it apart from other politically charged drug policies such as legalizing marijuana.

That distinction was made clear by Councilmember David Leinweber, who said at the city council meeting both that marijuana is “literally killing our kids” and that he supported greater access to psilocybin therapy.

Psilocybin is far more restricted in Colorado than marijuana, which the state legalized in 2014. Psilocybin is decriminalized but there won’t be recreational dispensaries for the substance, which will be largely confined to licensed businesses and therapy sessions with licensed facilitators.

Patients will have to go through a risk assessment, preliminary meetings, then follow-up sessions and remain with a facilitator while under the drug's influence. The psilocybin will also be tested, and the companies that grow them regulated by a state agency.

Still, allowing broader access to the treatment hasn't been easy for most of the city councilmembers, including three members who are veterans. Colorado Springs is home to two Air Force bases and the U.S. Air Force Academy, and local leaders frequently tout it as an ideal community for retired servicemembers.

“I will never sit up here and criticize a veteran for wanting to find a medical treatment to fix or to help with the issues that they carry,” said Council President Randy Helms, a veteran himself.

Still, he continued, “Do I think that it’s helpful to not just veterans but to individuals? Probably so. Do I think it still needs to be tested under strict requirements? Yes.”

The Colorado Springs city council passed the proposed restrictions.

While research has shown promise for psychedelic drugs such as psilocybin and MDMA, also known as molly, in helping people with conditions such as alcoholism, depression and PTSD, the scientific field remains in its relatively early stages.

“I’m very positive about the potential value, but I’m very concerned that we’ve gotten too far ahead of our skis,” said Jeffrey Lieberman, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, who's been involved in studies of psychedelic drugs' therapeutic efficacy.

The risks, said Lieberman, include customers being misled and paying out of pocket for expensive treatments. He also said there are cases where the drugs can exacerbate some extreme mental health conditions, such as schizophrenia.

In Oregon, where the treatments started in June 2023, costs can reach $2,000 for one session. Of the over 16,000 doses administered in the state, staff have only called 911 or taken a patient to the hospital five times.

Other Colorado Springs city councilmembers raised concerns that the Food and Drug Administration has not approved psilocybin to treat mental health conditions and, in August, rejected the psychedelic MDMA to treat PTSD. A number of clinical trials are still underway for both drugs.

Some researchers, advocacy groups and veterans worry that waiting on slow-moving bureaucracy — namely the FDA — carries its own risks as people continue to struggle with mental illnesses. Advocates argue that psychedelic therapy offers an option to those for whom talk therapy alone and anti-depressants have not helped.

“This is a crisis that we are in, and this is a tool that we can add to our toolbox,” said Taylor West, executive director of the Healing Advocacy Fund, which advocates for psychedelic therapy.

Belone said he's carried his military experience long after leaving the special forces. It started when he first heard artillery sirens wailing in a U.S. base in Iraq, his breath catching with fear for a few thudding moments.

That fear kept him on edge when he returned stateside and found himself always keeping his back to the wall, looking for exits to the room he was in, never quite able to give himself fully to the music at a concert.

A psychedelic experience with psilocybin, said Belone, helped him connect the fear that attached to him in the warzone to the ceaseless anxiety at home — it didn’t solve everything overnight, he said, but it allowed him to better identify when that humming fear was getting in the way of a joyful life.

___

Bedayn is a corps member for the Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.

Jesse Bedayn, The Associated Press