British Columbia’s first recognized native dinosaur is back home at the Royal B.C. Museum after travelling back and forth across Canada.

Ferrisaurus sustutensis made its world debut today in the peer-reviewed scientific journal PeerJ — the Journal of Life and Environmental Sciences.

Distantly related to triceratops but smaller and lacking the horns and armoured neck frill, ferrisaurus was about the size of a modern bighorn sheep. It weighed about 150 kilograms and lived 67 to 68 million years ago in the prehistoric redwood forests of northern B.C.

Victoria Arbour, curator of dinosaurs at the Royal B.C. Museum, and David Evans, paleontologist at the Royal Ontario Museum, are co-authors of the newly published description of the dinosaur they named after the area where it was found, the Sustut River basin.

Arbour said the few fossils of the creature’s bones were first collected in 1971 by a geologist working near the Sustut River, where forest clearing and blasting for a new rail line had exposed underlying rock. The geologist kept them for several years before donating them to Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia.

Arbour, who was interested in paleontology, examined them while at Dalhousie as an undergraduate in 2006. Recognizing them as belonging to something special, she lobbied to have them sent back to the Royal B.C. Museum.

“I just thought it made sense for the specimens to be at the provincial museum where they could be stored properly,” said Arbour. “Little did I know I would eventually make my way back here to study them in more detail.”

Before she arrived in Victoria in 2018 to take her post, Arbour did post-doctoral work at the Royal Ontario Museum. There, she met Evans, who had done his own work on leptoceratopsids, the line of dinosaurs to which the ferrisaurus belongs.

Remembering the specimens she had arranged to have transferred to the Royal B.C. Museum, Arbour raised them with Evans and the two got to work.

Arbour said she interviewed the geologist who collected them. He had good notes to identify the site where they were found, which was fortunate, since GPS was not widespread technology when he picked up the fossils.

In 2017, she led an expedition back to the Sustut area to look for more of the fossilized skeleton. No more bones were found, but pieces of a turtle shell and some fossilized plants were collected, offering clues about the creature’s habitat. “I am hoping in the future we may find a more complete skeleton of this particular dinosaur,” Arbour said.

She and Evans had concluded that one of the fossils collected in 1971 was a toe bone belonging to a ferrisaurus, based on its stubby shape and distinctive claw.

“We would sit down and take a look at the fossils, argue about them, discuss them with each other,” said Arbour. “It was really great to be able to collaborate with David. He is a very knowledgeable dinosaur person.”

Arbour then made trips to the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana, and the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis, all of which had relatively complete skeletons of ferrisaurus species for comparison.

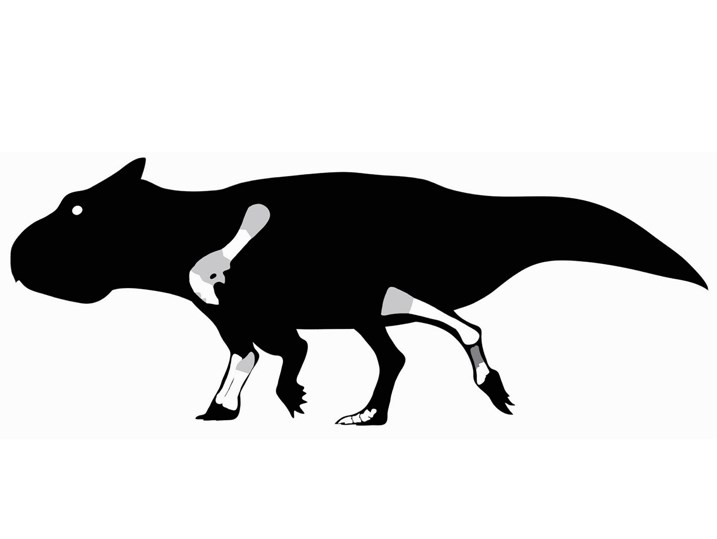

Extrapolating from those skeletons and working from the specimens collected in B.C., the two scientists were able to put together a likely approximation of Ferrisaurus sustutensis.

The creature is believed to have had a parrot-style beak and lived as a plant eater. But little else is known, since relatively few fossils have been collected.

“It probably walked on four legs most of the time, but might have walked on two legs some of the time,” said Arbour. “It had a short stubby tail instead of a long slender tail like some dinosaurs.

“It’s a group of dinosaurs we still don’t know an awful lot about. That’s another thing that’s pretty cool about this species.”

The fossils of the Ferrisaurus sustutensis, which Arbour has nicknamed Buster, are on display until Feb. 26 at a pocket gallery called B.C.’s Mountain Dinosaur on the main floor of the Royal B.C. Museum. The display is open to the public, free of charge.