Previous chapter [“The fire,” October 18]: in the spring of 1949, Nancy Crowther received a horrible shock when she returned home from work in Powell River to find their cabin in Penrose Bay engulfed in flames. Her home since 1927 went up in smoke, and her family lost almost everything, but no lives were lost or injuries sustained. Neighbours emerged from the inlets to help rebuild, and soon, a sturdy log cabin was built, the one that remains on the property to this day, but the Crowthers needed money to replace all that they had lost.

Oysters. That was the idea Nancy’s father Bill had come up with while chatting with another neighbour.

The oyster that is native to the Okeover Inlet and Desolation Sound area is small and clings flat to the rocks, making it very difficult to harvest. But the Pacific or Japanese oyster, which had been making its way into BC coastal waters thanks to an influx of Japanese fisherman and homesteaders for years, grew in a much larger size, some as big as a basketball player’s shoe.

They were easy to pick up, and multiplied quickly in our warm coastal inlets, especially in Desolation Sound, which boasts not only the warmest water in the Salish Sea, but reportedly the warmest ocean water in all of North America north of the Gulf of Mexico.

Nancy Crowther’s father and his neighbour were arguably two of the first European pioneers to bring in Japanese oyster seeds to the Desolation Sound area, applying for an oyster lease from the government for the beaches ringing their properties. Soon they started farming. The oysters spread so rapidly that the large, white “laughing oyster” that is ubiquitous throughout our inner coast is often not realized to be an invasive species.

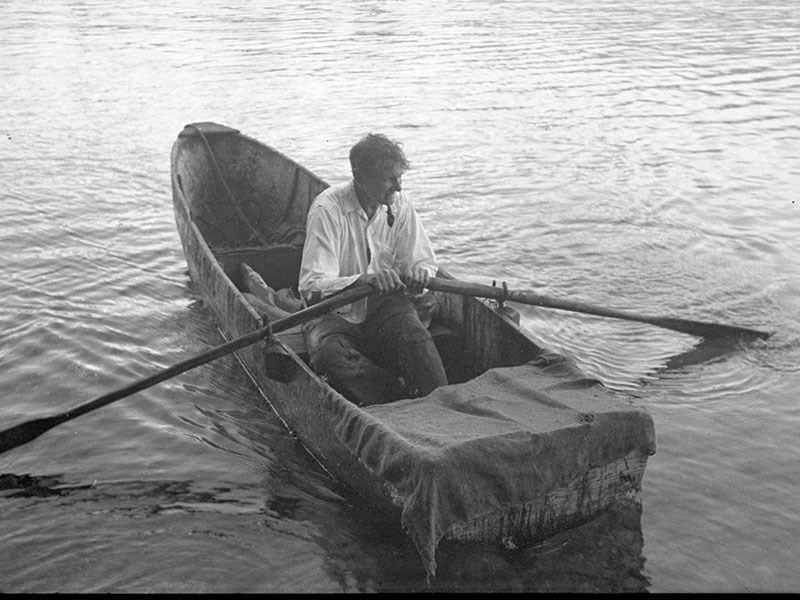

Oyster farming took off as a money-making industry in Okeover and Desolation Sound in the prosperous 1950s, and soon, Nancy Crowther was spending her weekends being paid to farm oysters for a local processing plant that had opened up down the inlet from her family homestead.

By the 1950s, Nancy’s reputation for being an unlikely cougar killer was known far as wide, but as noted earlier, she did not welcome her celebrity. She was always wary that other people were staring at her and talking about her. Maybe they were, but maybe they weren’t. It was a seed of paranoia that would grow and come to haunt Cougar Nancy in her later years.

One day, while working out on the oyster floats, she likely suspected this very thing from some of her co-workers, three girls who were working on another nearby float. Mary Masailles from Craig Road was one of those girls.

The CBC’s Willow Yamauchi, who grew up in Lund, interviewed Mary about “Cougar Nancy” years ago, before Mary passed on.

“There were two floats; Nancy was on one float and three of us were on the other float,” remembered Masailles. “Anyway, all of the sudden, something was slung at me, and it hit me in the back of the leg. Oh god, my leg was bleeding. And you know what, she threw a starfish, and you know how sharp they are. It cut me wide open.”

Supposedly out of the blue, Nancy had thrown a large purple ochre sea star, which left Mary cut and bewildered.

“I don’t know why she threw the starfish!. It was in the summertime, and we just had running shoes on, and a pair of shorts,” recalled Masailles. “Then I realized my shoe was full of blood. That’s when Tiny, one of my girlfriends, says to me ‘don’t worry, Mary, we see it. Don’t worry, say nothing.’ So I just kept my mouth shut.”

Mary and the other girls were dressed in casual summer wear for young women in the 1950s: shorts, blouses and sneakers. Cougar Nancy, a child of the wilderness, was in her regular plain dress and rubber boots. There were no more incidents on the oyster floats until the end of the day, when Nancy struck again.

“We had the floats full,” recounted Masailles, “so it was time to come back, and Nancy had to get in the same boat as we did. So we piled all the pales in. I get into the boat, then Nancy gets in, and Tiny is standing next to the boat. As she lifts her leg up to get in, oh! Into the chuck Tiny went, ass first.”

Nancy had suddenly grabbed Tiny’s foot and hoisted her up, knocking her off balance and into the ocean.

“She was soaked,” said Masailles.

And while many considered Cougar Nancy to be shy and soft-spoken, an offset to her fearless cougar hunting ways, her family knew otherwise. Cougar Nancy had a temper, and was prone to what the family referred to as “blow ups.” Those who were around at the time remember that Nancy’s calves and biceps were like cannonballs. You didn’t want to mess with Cougar Nancy Crowther, and Mary confirmed it.

“Oh, she was violent,” exclaimed Masailles. “She was wild! So, anyway, we got all the stuff back over to the plant, and they all got out of the boat, all but me. My arms are full with lunch pales and one thing or another. Nancy’s holding the boat’s rope and then she says to one of the boys, ‘here, take this rope, I got a score to settle with Mary.’ When I got onto the dock, she grabbed me. And I had a blouse on, and in those days the blouses buttoned down the back. Well, she grabbed me and off came my blouse. So I’m standing there on the dock in a bra,” chuckled Masailles. “She threw my blouse out in the chuck, eh? And then she was going to kill me!”

There was Mary Masailles, standing on the dock at the oyster processing plant in Okeover Inlet wearing nothing but a bra and her shorts, with one shoe filled with blood, and Cougar Nancy wasn’t done. With her cannonball biceps bulging, Nancy charged like a bull at Mary.

What did Mary do? What would you do?

That’s in the next chapter of the Cougar Lady Chronicles.

Grant Lawrence is an award-winning author and a CBC personality who considers Powell River and Desolation Sound his second home. Portions of the Cougar Lady Chronicles originally appeared in Lawrence ’s book Adventures in Solitude and on CBC Radio. Anyone with stories or photos they would like to share of Nancy Crowther are welcome to email [email protected].